By Jonathan Hersch, MD

Introduction

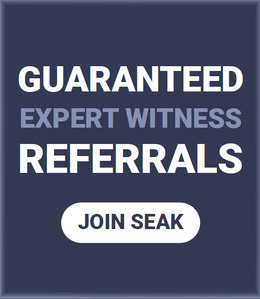

A large percentage of the population is walking around now with meniscus tears (aka cartilage tears) in the knee without knowing it. Many people currently have rotator cuff tendon tears in the shoulder but don’t know it. Many people have herniated discs in the neck, and low back yet don’t have symptoms. Almost everyone as they get older (50 +) has “abnormal findings” on an MRI, which are, in fact, normal.

Orthopedic expert witnesses are often called upon to determine the causation of shoulder injuries.

MRI Machines

MRI, magnetic resonance imaging, is a fantastic tool to see intricate parts of the human anatomy. All MRI machines are not the same. Their strength and ability to see detail, especially of small structures like the labrum in the shoulder, measure in units called Tesla. Tesla is the unit of measurement that defines the strength of the magnetic field. MRIs come in open and closed units. Generally, closed units offer higher Tesla, 1.5T, and 3.0T providing higher quality imaging for a more accurate diagnosis. Open MRIs should be reserved for claustrophobic patients who absolutely can’t get into a closed unit. However, these Open MRIs have lower strength and offer inferior image quality.

As you can see from this diagram below, many people can have abnormal findings, yet no symptoms.

Rotator Cuff Tears

One of the most common findings on a shoulder MRI is a rotator cuff tear. A tear can be a partial tear or a full tear. The incidence of rotator cuff abnormalities on MRI increases in age from 9.7% at age 20 and under to 67% over 80 (1). Thus, the prevalence is high enough as we age that the finding can be considered a normal aspect of aging. It is difficult to determine when an abnormality is new (i.e., after a dislocation) or the cause of symptoms.

Degenerative Rotator Cuff Tears

So-called “degenerative rotator cuff tears” that develop due to age that are not symptomatic can enlarge over time and eventually develop symptoms with or without injury. (2)

Many patients with full-thickness rotator cuff tears do not need surgery even if symptomatic. (3). Choosing the right patient to operate depends on many factors. One study showed that patients presenting with a symptomatic full-thickness rotator cuff tear had a 35.5% prevalence of a full-thickness tear on the contralateral shoulder. On average, the symptomatic tear was 30% larger. (4)

Some findings can be interpreted as normal findings for age, like tendinosis but may also be interpreted as a “partial tear.”

The black arrow points to a thick rotator cuff with an abnormal grey signal and read as a partial tear by a radiologist.

The white arrow points to the rotator cuff tendon, thick and entirely grey, read as tendinosis.

I call this the “grey hair of the shoulder.” Tendons turn grey on MRI when they age. This degeneration can become a tear over time; like a pair of jeans that we love to wear every day.

Causation and MRI findings

Orthopaedic surgeons will almost always order an MRI on a patient who is not getting better from an injury. Interpreting this in light of the patient’s history and examination is an art that takes years of experience.

An Orthopaedic surgeon expert witness must evaluate injured patients who suffer so-called tears, bulges, or herniations. It is an art and a science to diagnose a condition correctly. Findings on MRI are not always the cause of pain in a patient. Many MRIs may have multiple “abnormalities.” The shoulder is a typical example where a report may read “rotator cuff tear,” “labrum tear,” and “biceps tendon” injury. Some, all, or none of these findings may explain a patient’s symptoms.

Occupational Risk Factors for Rotator Cuff Disease

These changes on MRI of tendinopathy and tears of the rotator cuff are often linked to the individual’s activity or employment. Research is scarce linking work as a cause of rotator cuff disease. According to the AMA guides, there is “some evidence” to support a combination of risk factors (i.e. force and repetition, force and posture) and highly repetitive work. There is “strong evidence” of awkward positions with shoulder-sustained postures with more than 60 degrees of flexion/abduction. (5).

Non-occupational Risk Factors for Rotator Cuff Disease

Patients have factors that cannot be controlled for when planning treatment for shoulder disorders. According to the AMA Guides, there is strong evidence to support advancing age, higher BMI, and some evidence for Diabetes as risk factors for the development of symptomatic rotator cuff disease. Surprisingly, the dominant hand is not a risk factor. (6)

Rotator Cuff Tears

For Rotator Cuff tears, we look for several things on MRI to aid in the “aging” of a tear. It is not exact, but we know that tears don’t follow the same timeline as symptoms. Tears that may be chronic (months – years) have several characteristics on MRI.

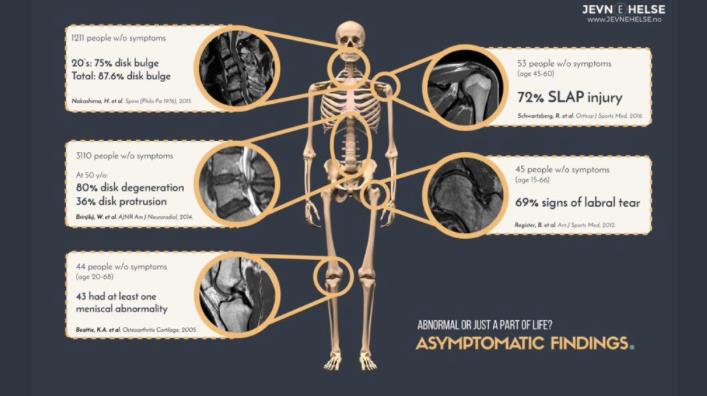

Retraction of Tendon

This MRI shows a large retracted tear indicated by the orange line showing the distance from the tendon edge on the right to the attachment site on the left.

photo courtesy of mattdriscollmd.com

High Riding Humeral Head

This MRI shows the humeral head is in contact with the acromion, a so-called high riding humeral head, which implies the cuff is no longer functioning. It has allowed the humerus to migrate proximally. X-ray on the right shows a similar finding.

photos courtesy of radiologykey.com

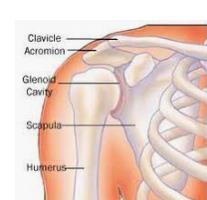

Anatomy for reference

Photo courtesy of en.wikepedia.org

Fat Atrophy of Muscle

A retracted, chronic rotator cuff tear will not function. Eventually, the muscle will turn to fat on MRI. When this occurs, it usually indicates the tendon is not repairable and will not heal. In the rare case that a surgeon can repair the tendon, the reversing of the fat atrophy usually does not recur.

In this MRI, the Subscapularis muscle (Su) looks normal, uniformly dark. The Supraspinatus (SS) is surrounded by fat (outlined in yellow B), indicating moderate atrophy. The grey streaks in the Infraspinatus (IS) and Teres Minor (Tm) shows early fatty infiltration.

photo courtesy of journals.sagepub.com

Labrum Tears

The labrum is the lining of the shoulder’s socket where the ligaments and the long head of the biceps attach.

photo courtesy of orthoinfo.aaos.org

A SLAP (superior labrum anterior-posterior) tear occurs when the biceps’ long head pulls on the superior portion of the labrum, and it comes apart. There are various types, with the most common being type 2, as shown in the above diagram. Determining what kind of labrum tear is present on MRI is challenging. Often, signal changes in the labrum are called “tear” by a radiologist when, in fact, it is normal changes. Also, there are a fair amount of normal variants of the labrum that mimic tears on MRI. (6). It has been shown in many studies that clinical examination is more accurate than MRI in predicting labral tears. (7) It turns out the gold standard and most accurate way to diagnose a labrum tear are at the time of arthroscopic surgery.

The MRI on the left shows the superior labrum attached to the socket. On the right, the labrum is detached. Enhancement by the addition of dye injected into the shoulder (white area) helps make the diagnosis.

photo courtesy of orthoinfo.aaos.org

Conclusion

Orthopedic surgeons are often called upon to opine on causation for patients with shoulder injuries. These surgeons who read the MRI, understand the occupational and non-occupational risk factors for shoulder injuries, and conduct a comprehensive exam and history, are well-positioned to opine on causation.

About to Author

Jonathan Hersch, MD, is a board-certified orthopedic surgeon and expert witness who trained at the world-famous Cleveland Clinic. He has extensive experience in speaking/lecturing at national and international meetings. He can be reached at jhersch1@gmail.com or 954 464-7513.

Bibliography

1 Teunis, T, Lubberts B, Reilly B et al. A systematic review and pooled analysis of the prevalence of rotator cuff disease with increasing age. JSES 2914 Dec;23(12):1913-1921.

2 Keener J, Galatz, L, Teefey S. et al. A prospective evaluation f survivorship of asymptomatic degenerative rotator cuff tears. JBJSAm 2015 Jan 21;97(2):89-98.

3 Boorman R, More K, Hollinshead R et al. What happens to patients when we do not repair their cuff tears? Five-year rotator cuff quality of life index outcomes following non operative treatment of patients with full thickness rotator cuff tears. JSES 2018 Mar; 27(3):444-448.

4 Yamaguchi K, Ditsios K, Middleton WD, et al. The demographic and morphological features of rotator cuff disease. A comparison of asymptomatic and symptomatic shoulders. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2006;88(8):1699-1704.

5 Melhourn JM, Talmage J, AckermanW, et al. Shoulder tendinopathy, Impingment and Rotator Cuff Tears in AMA Guides to the evaluation of Disease and Injury Causation. 2nd Edition. Pp318-355.

6 De Coninck, Ngai SS, Tafur M, et al. Imaging the glenoid labrum and labral tears. Radiographics 2016 Oct;36(6):1628-1647.

7 Liu SH, Henry MH, Nuccion et al. Diagnosis of glenoid labral tears. A comparison between MRI and clinical examinations. Am J Sports Med Mar-Apr 1996;24(2):149-154.