By Susan Abookire, MD MPH FACP

Introduction

A missed or delayed diagnosis, particularly of cancer, can lead to malpractice litigation. In one study of five malpractice insurance companies across four regions of the United States, (Northeast, Mid-Atlantic, Southwest, and West), the authors found that 29% of claims with injuries (and a determination of error) were related to missed or delayed diagnosis.[1] In another broad evaluation of closed claims from four malpractice carriers across three United States Regions, 30% of claims studied were categorized as missed or delayed diagnosis.[2] A healthcare systems expert witness can add value to a medical malpractice claim by evaluating the procedures in place to help prevent delayed diagnoses.

How can a diagnosis become missed or delayed?

The diagnostic process spans a series of events:

- a patient seeks care

- a provider recognizes the problem

- the provider correctly plans next steps

- the appropriate diagnostic testing is ordered and completed

- diagnostic tests such as radiology images are interpreted correctly

- findings are communicated reliably

- the correct follow up is arranged and successfully carried out in a timely fashion.

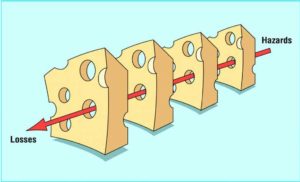

Sometimes a missed or delayed can result from a clinical judgment error. For example, physician fails to perform a physical examination and develop a differential diagnosis of a woman’s back pain when she presents ill with fever; the result is a delayed diagnosis of spinal infection and sepsis. More often, however, preventable delays result from a series of breakdowns in the diagnostic process. In the field of patient safety, the well-known ‘swiss cheese’ metaphor developed by psychologist James Reason[3] depicts how a system has processes in place to assure safe outcomes (the cheese), but that ‘holes’ in these systems represent hazards that, when they align and occur in sequence, may result in harm, and even death, that is preventable. This model depicts why reliable safety systems in healthcare organizations are necessary to assure safe outcomes. A healthcare systems expert witness can identify breakdowns that led to harm, and evaluate the breakdowns compared with standard of care.

Since diagnostic delays unfold over time, they often appear to occur in the outpatient setting. Suppose a gentleman in his 40’s sees his primary care physician and reports having had blood in his stool and the patient thinks it’s his hemorrhoids. The physician may reassure the patient and tell him to return if the bleeding persists. However, if the physician fails to obtain a thorough history that includes night sweats, weight loss, and a family history of colon cancer, this may be the first failure in a delayed workup and diagnosis of colon cancer. Or, a logistical or ‘system failure’ may occur when the physician refers the patient for a diagnostic colonoscopy to check for colon cancer, but the referral either doesn’t go through to the specialist, and there’s no system in place to detect that this diagnostic testing failed to occur. When the gentleman is later found to have advanced colon cancer, litigation begins. A healthcare systems expert can identify standards of care for safety procedures.

The hospital or emergency room can be the site for an initial system failure. Suppose a patient goes to the emergency room with abdominal pain, where a consulting urologist orders a CT scan that confirms and locates a kidney stone. In addition to the stone, the radiologist notes an “incidental finding” of a 1.5- centimeter opacity in the lower lung that raises the possibility of cancer and warrants a follow up CT in six months to re-evaluate. This is known as an actionable “incidental finding;” incidental findings are findings on imaging (or other tests) that are unexpected and unrelated to the purpose of the original testing, that require some action. If these findings are not actively managed with procedures and policies, they can ‘fall through the cracks’ and cause missed or delayed diagnoses. A reliable institutional or system level policy identifies the physician responsible for this follow-up; for example the ordering urologist, the emergency room physician, or the primary care physician.[4, 5] Incidental findings, like other critical results, are best communicated in a manner such that communication ‘closes the loop:’ the information is not only sent, but also received, acknowledged, and understood by a responsible provider, and also communicated to the patient.

Conclusion

Substantial malpractice claims occur for delayed or missed diagnoses. Failures can occur at multiple points, and may stem from failures of judgment, handoffs, communication, or follow up. Healthcare system safety processes exist to mitigate this risk. A healthcare systems expert witness may be a valuable resource to address organizational standard of care in a medical malpractice case.

About the author:

Susan Abookire, BSEE, MD, MPH, FACP, is an Assistant Professor at Harvard Medical School and a senior executive with 20 years’ experience leading healthcare organizations. She has led award-winning safety and quality programs, and has served as Chief Medical Officer, System Chief Quality Officer, and Chair of Department of Quality and Patient safety. Dr. Abookire began her career as an electrical engineer in aviation systems. A graduate of Harvard Medical School, Dr. Abookire trained at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, a Harvard teaching hospital, and continues to practice there. Dr. Abookire received a master’s degree from the Harvard School of Public Health. She co-founded the Harvard Medical School Fellowship in Quality and Patient Safety, and has taught nationally and internationally on patient safety, health technology, human factors, high reliability, systems design, adverse event learning systems, and applying aviation lessons. Dr. Abookire has served as an expert witness in hospital and healthcare organizational systems.

Contact Dr. Abookire at: 617-549-9405, abookiremd@gmail.com.

- Studdert DM, Mello MM, Gawande AA, et al. Claims, errors, and compensation payments in medical malpractice litigation. N Engl J Med. 2006;354(19):2024-2033.

- Gandhi TK, Kachalia A, Thomas EJ, et al. Missed and delayed diagnoses in the ambulatory setting: a study of closed malpractice claims. Ann Intern Med. 2006;145(7):488-496.

- Reason J. Managing the Risks of Organizational Accidents. Brookfield, VT: Ashgate; 1997.

- Kwan JL, Singh H. Assigning responsibility to close the loop on radiology test results. Diagnosis (Berl). 2017;4(3):173-177.

- Baccei SJ, Chinai SA, Reznek M, Henderson S, Reynolds K, Brush DE. System-Level Process Change Improves Communication and Follow-Up for Emergency Department Patients With Incidental Radiology Findings. J Am Coll Radiol. 2018;15(4):639-647.